The team behind Luca were facing a unique challenge: water. It wasn’t a matter of making the water in the upcoming Pixar film look realistic and detailed — Pixar animators could probably create photorealistic water in their sleep. It was a matter of making it less realistic.

It’s a strange problem for Pixar to have, right? The animation studio had perfected 3D animation to such a degree that their films have started to look almost too realistic. But it’s a problem Luca director Enrico Casarosa was happy to have.

“The tools of the trade are getting better and better at capturing realism,” Casarosa said at a press presentation /Film attended for Luca earlier this month. “We wanted to work on stylization and beautiful shades and lyricism. So, that is the bit where we pushed the tools to do something a that they don’t necessarily want to do.”

It was a new challenge for Casarosa’s team: to go against their instincts toward realism (and against what Pixar’s programs were designed to do) and pursue the kind of stylization that Casarosa, through his playful watercolor storyboards, was aiming for. So they dedicated themselves to one major direction: capturing “the hand of the artist.”

“The hand of the artist, of course, starts with Enrico’s drawings,” production designer Daniela Stijleva told /Film. “They’re very gestural. they’re very imperfect, in the best possible way. They have life to them.”

From Polaroids to Pixar

Casarosa makes his feature directorial debut with Luca after impressing the folks at Pixar — including Luca producer Andrea Warren — with his lovely short film La Luna. But much like how the story of La Luna, which depicts a young moon-sweeper learning the tricks of the trade from his father and grandfather, was inspired by his relationship with his family, Luca is a deeply personal story for Casarosa that has been long in the making. Well, except for the sea monsters part, obviously.

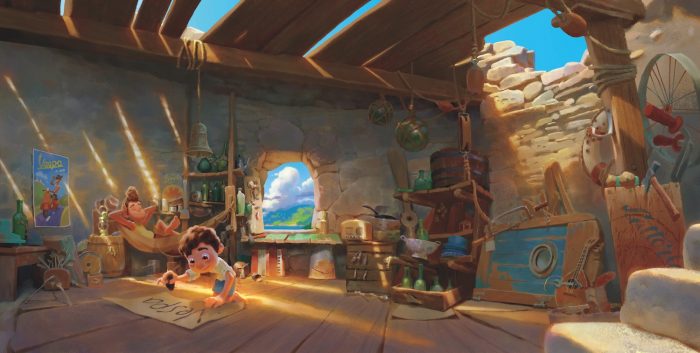

Luca follows the titular Luca, a curious young sea monster who is drawn to the bustling seaside town on the Italian Riviera by a fellow kid sea monster and Vespa enthusiast, Alberto. Alberto is everything Luca is not — gregarious where Luca is shy, adventurous where Luca is cautious. Alberto has created a little hovel for himself and his absent dad on the seashore out of knick knacks and human junk he’s recovered from the nearby town, and invites Luca to explore the surface world with him, where they transform into humans when they dry off. And when Luca balks, Alberto encourages him to silence the little voice telling him “no” in his head by shouting, “Silencio Bruno!”

“‘Silencio Bruno’ is from our writer Jesse Andrews,” Casarosa revealed during the press conference for Luca. But Alberto is based on Casarosa’s own childhood best friend, also named Alberto. The friendship between Luca and Alberto is not so subtly inspired by his own with Alberto, growing up in the port city of Genoa, on the Italian Riviera.

“He had a family that wasn’t there for him, and I had a family that was a little bit too much there for me. And I was timid and kinda shy, and he was following a passion every week,” Casarosa reminisced of Alberto, whom he stayed in touch with over the years. Casarosa recalled summers of gelato, pasta, and running through the sun-dappled streets of Genoa with Alberto, all of which was captured on grainy polaroids that the Luca team used as reference in crafting the film, in addition to their own research trip to Genoa, equally filled with gelato and pasta. Casarosa and Warren also called on the team to bring in their own childhood photographs as inspiration for the warm, nostalgic coming-of-age story of Luca.

And what does the real Alberto think of this?

“He’s a fighter pilot and he’s a colonel, so he’s actually had a very successful career,” Casarosa said. “And, now he’s [told me], ‘Hey, you better make me look good in this movie.’ But I’m trying to surprise him a little bit.”

We’re All Outsiders (and Sea Monsters) at Heart

So why sea monsters? To Casarosa and producer Warren, it was the perfect metaphor for feeling like an outsider, which made it the perfectly unique spin on this coming-of-age story. It’s literally ” a story of a fish out of water.” Casarosa said:

“We hope that sea monster could be a metaphor for all sorts of feeling different–like being a teen or pre-teen. That moment where you feel odd. There are all sorts of ways of feeling different. It felt like a wonderful way to talk about that and having to accept ourselves first, whatever way we feel different.”

Added Warren, “I think that we liked the idea always that the metaphor of being a sea monster can apply to so many different thing… There is a theme of openness and showing oneself and self-acceptance as well as community-acceptance.”

Visiting La Riviera of the 1950s

With Luca, Casarosa brings to life his childhood hometown of Genoa, at the center of La Rivieria, which was “a very specific coast because it’s really steep—the mountains rise up from the ocean. The towns are stuck in time—they’re so picturesque. I always imagined them like little monsters coming out of the water.”

The timelessness of the towns on the Riviera is what led to Casarosa deciding to place Luca in the 1950s instead of the ’80s, the period in which he actually grew up. “I think maybe because of the tube socks, the 80s seemed less interesting to me,” Casarosa said with a laugh, adding:

“It really was an aesthetic, beauty, and a musical choice, and then a timelessness. It goes to that same, answer I was mentioning before, to me, when you go to an older era, it can feel a little more timeless, and a little less specific too, just because it’s a little bit more removed for us.”

The setting of the ’50s and ’60s was also tied to the Italian cinema that Casarosa loves. The director cites the works of Federico Fellini as one of the influences on Luca, which is also full of Easter eggs to Italian filmmakers that Casarosa loves, like a poster of Pietro Germi’s 1961 movie Divorce, Italian Style.

“I was after, first of all, a period that I love,” Casarosa said. “So, part of it is just my love of that golden era of film and cinema in Italy. I love the music in all these coming-of-age stories of summer, music is a huge, huge part of a movie. So, I just love the music of the 50s and 60s in Italy, so we’re using a lot of that. And then the design, the old Vespas, the old, little carts-bicycle, I just love the sense that this has an old feel.”

But even with that nostalgic sheen over Luca, the movie is still specifically, painfully, Italian. Apart from the main voice cast led by Jacob Tremblay as Luca, Jack Dylan Grazer as Alberto, and newcomer Emma Berman as their reluctant human friend Giulia, the supporting cast of Luca is almost entirely staffed by well-known Italian actors, including Saverio Raimondo, Marco Barricelli, and Marina Massironi. The Luca team even met with their Disney Italy colleagues over Zoom to get the hand gestures for the characters just right. The session ended with everyone swearing heavily in Italian, which sadly did not make it into the movie, for obvious reasons. But what did make it into the film were the little details: the Ligurian dialect, and a “little [bit of] Genoa,” Casarosa said. For example, ” We wanted as much focaccia in this movie as possible. Focaccia is our bread.”

He continued, “I have so many little details that I’m, like, ‘Ooh, this one is very specific and people in Liguria would probably understand.'”

The Challenge of Animating “Simplicity”

Casarosa clearly had a very specific vision in mind for Luca, one that came across in his watercolor storyboards and his nostalgic ’50s setting. “His drawings, a lot of that inspired the look of the film,” production designer Daniela Stijleva said. “Because of the desire to make it illustrated, to make it like a children’s book or to inject that kind of hand of the artist.”

But that provided a unique challenge for the animators, designers, and effects team at Pixar, whose software is designed for realism. For Stijleva, that meant having to alter the technology to make it imitate a more stripped down 2D-inspired style:

“We can make real water very quickly. We don’t have to do that, but to strip down certain details and to make it more stylized, it’s actually really difficult. Because then it becomes non-believable. You and I know what water looks like. So, if you remove certain details from it, you’re gonna tell me that doesn’t look like water anymore, it doesn’t feel right doesn’t look the right way. So [effects supervisor] Jon [Reisch] and his effects team had to work so hard to make it believable never to lose the audience but also to make it poetic and kind of like it has the hand of the artist.”

“It took a lot of just kind of winding un-wiring our Pixar brains, and sort of rewiring in this new way,” Reisch said, of toning down the detail to reflect that simpler style. To help them in that process, Casarosa pointed them to the works of Studio Ghibli for inspiration, and interestingly, Japanese woodblock prints:

“That was a big inspiration for us, just in terms of the kind of detail we wanted to capture across the surface of the ocean, in those beautiful woodblock prints. We were just looking at areas in those paintings where there’s a lot of detail, and in areas where there’s almost no detail it’s just suggested in certain places, and just how beautifully that directs the eye.”

The result can be seen in the storybook-like water, which has much fewer ripples than its photorealistic counterpart, and in the staccato movement of the characters, which move and pose much more like 2D and stop-motion characters — the team even using such old-school 2D animation tricks as multi-limb effects (the kind of pinwheel running you’d see in a Looney Tunes show or older cartoons). It’s a new more “lyrical” style of animation for Pixar that Reisch hopes will continue in 3D animated movies.

“I just think that’s such a cool way to, to move innovation forward and not really feel like we’re have to be bound to produce this more photorealistic but I think that’s one of the beauties of working in animation is that we can use all the expressive tools that we have at our disposal to create something that’s really unique kind of support the story we’re telling,” Reisch said.

***

Luca will begin streaming exclusively on Disney+ starting June 18, 2021.

The post With ‘Luca,’ Pixar is Moving Away From Realism and Toward “the Hand of the Artist” appeared first on /Film.

0 Comments