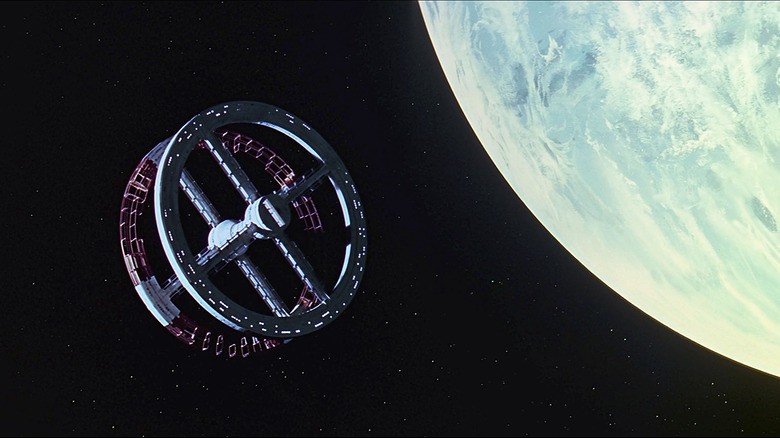

Stanley Kubrick's 1968 feature film "2001: A Space Odyssey" is -- and I know this appellation is tossed about freely, but in this case it's warranted -- one of the best films ever made. Written by Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke, it is one of the few films to reach out and scrape its fingernails against the infinite. It points out to us gravity-bound near-primates that we are only in our infancy when it comes to the vast weft of the cosmos' incomprehensibly large arc of time. Our next step in evolution -- a process just as fraught with violence and death as it is growth and innovation -- will be to reach our minds deep into the vastness of space and try, in our tiny way, to extend into it.

My view of "2001: A Space Odyssey" is, however, not shared by all critics, and audiences in 1968 weren't all universally kind. The initial wave of reactions to "2001" were marked by puzzlement and confusion, with some critics and viewers lambasting Kubrick and Clarke for being intentionally opaque. A modern analog may be the audience's reactions to films like "Inception" or "Tenet." Namely: It's pretty, and distantly intriguing, but what are you driving at?

Here, then, is a brief history of the critical and audience reaction to "2001: A Space Odyssey."

What The Hell?

This is a matter of record: At the film's 1968 premiere, 241 people walked out -- including Rock Hudson, who was heard to say, "Will someone tell me what the Hell this is about?," or, more colorfully, "What is this bulls***?" Although that may be apocryphal.

Indeed, the general atmospheric attitude immediately after the premiere was that Kubrick had made an impressive technical achievement without making an actual, y'know, movie. This was not traditional mainstream entertainment, but a heady and ambitious work of art and philosophy. Which, as a cynic might take as a given, was not embraced by mainstream audiences. Kubrick ended up shortening the film by a good 20 minutes after the premiere. According to those in the know, all that was lost was a second Pod sequence similar to the first. As it stands, the 140-minute version doesn't feel incomplete.

Most critics at the time noted "2001's" notorious opacity, whether to praise or lambast it. The New York Times review of it placed it somewhere between majestic and boring. Roger Ebert noted that there were many walkouts at the premiere (which he attended), but defended the experience, knowing that those with patience had witnessed something profound and significant. Critic Joe Morgenstern of Newsweek was particularly harsh, however, saying the film begins as "a whimsical space operetta, then frantically inflates itself again for a surreal climax in which the imagery is just obscure enough to be annoying, just precise enough to be banal." I admire Morgenstern, but ouch.

Anecdotally, this has been the reaction from many peers of mine throughout my own life as well. Some friends and colleagues have said they love the music, the imagery, and the groundbreaking special effects in "2001: A Space Odyssey," but begin to flounder when asked to explain the film's themes or even basic elements of its story. As one friend pointed out, it's the only sci-fi epic with an extended period in the pre-human world (although since that statement was made, we also witnessed Terrence Malick's "The Tree of Life"). Another peer, to this day, calls the film the biggest waste of time he's ever spent in a theater, and this was a friend I saw "Spawn" with.

The 1968 review in The Guardian exemplifies the mixed attitudes of the time, calling it beautiful to look at, but missing a certain spark of originality, and most certainly impossible to penetrate. The critic felt that Kubrick and Clarke hadn't thought things through.

Jupiter And Beyond The Infinite, Man

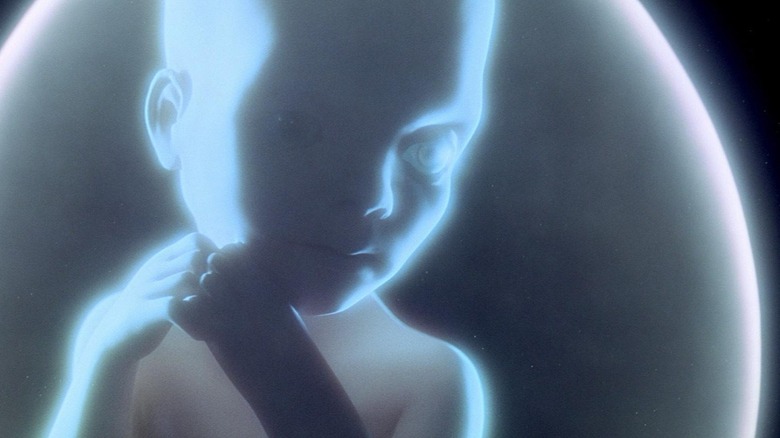

There was also a secondarily appreciative audience for "2001: A Space Odyssey" that perhaps keyed into its sense of the infinite, and most certainly had a deep appreciation for the film's overwhelming and psychedelic visuals: Young hippies. "2001: A Space Odyssey" plays with an intermission, and the second half of the film contains a chapter called "Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite," which is an extended sequence of lights and photographic effects depicting the character of Dave (Keir Dullea) sinking into ... another dimension? A new state of mind? An alien world?

Theater owners would carefully monitor ticket holders as they entered the theater, but in many theaters, such scrutiny was not provided during intermission, allowing people to sneak in unfettered. Hippies zonked out on weed or LSD could then slip in undetected, lay down on the floor in front of the screen, splayed in the sold-out auditorium, and allow the colors and sounds to wash over them. This is not, perhaps, how Kubrick intended his film to be viewed -- only the second half and likely high on God-knows-what -- but there was, at least an appreciative audience.

To speculate: This appeal to "hippie" sensibilities -- that is: lack of rollicking thematic clarity, psychedelic images, perhaps linking science to the spiritual -- may be what kept squares away in the film's early life. Those 241 people who walked out of the premiere, like Rock Hudson, perhaps all muttered that it was just beyond them, that it didn't make sense, and, perhaps, that it was only for those who had been chemically altered.

The Pod Bay Doors Re-Opened

Eventually, "2001: A Space Odyssey" was a hit. On a $10.5 million budget (which translates to about $83.5 million in 2021 dollars), it made about $56.7 million (about $450 million in 2021). And while the New York critics were harsh, the Hollywood critics gave it raves, leading to an eventual reputation as one of the more significant films of the year and, eventually over the next few years, one of the best films of all time. "2001: A Space Odyssey" still regularly tops lists of the best sci-fi films of all time, coming in 6th on the best top-ten poll running, the once-a-decade Sight & Sound Greatest Films of All Time poll (wherein a battery of hundreds of professional critics and filmmakers submit top-ten lists).

Your own personal journey with "2001: A Space Odyssey" may mirror audience's initial reaction. You may find the film to be slow-moving, strange, and intentionally difficult to understand. You may feel a twinge of annoyance when you hear the quote from Arthur C. Clarke where he said it wasn't meant to be fully understood. You may resent it. And then you may live with it a while, considering its influence, its ideas, its view of evolution and of space travel. Its profound combination of optimism about the future and pessimism about the human condition. You may, after a few years, finding it rising in estimation. If the audiences at its premiere were any indicator, you may be on a path to appreciation.

(Watch all the films on that list Sight & Sound, by the way. The next list is due next year. I have not yet been asked to participate.)

Read this next: The 14 Greatest Science Fiction Movies Of The 21st Century

The post The Brutal Reaction Audiences Had to 2001: A Space Odyssey's Premiere appeared first on /Film.

0 Comments