For over a year now, many of us have been stuck in the same location: doing remote work, going out and traveling less, living like cloistered movie monks. Everyone has their own personal quarantine stream and we’ve already seen the Zoom-based horror film Host explore a confined, coronavirus-adjacent narrative. Even before the pandemic, however, there was a robust tradition of filmmakers shooting one-location features on a low budget. Often, these were first-time directors striving for innovations amid limitations. The claustrophobic setting was perhaps their best chance to get a movie made and be in control of all the variables involved. Fewer locations, fewer setups, fewer chances for things to go wrong.

This last week alone has seen the release of no less than four single-location movies. On Netflix, there’s Oxygen, which seals Melanie Laurent inside a cryogenic pod, and The Woman in the Window, which has Amy Adams playing a homebound agoraphobic. On VOD, there’s The Djinn, which traps a mute boy in his apartment with an evil genie. In theaters, there’s Profile, which uses Screenlife as the basis for a terrorist thriller. If any of these flicks put you in the mood for the cinematic equivalent of a chamber play, here are 10 more titles that deserve an immediate spot on your to-view list.

A note about methodology: this a chronological listing, not a ranking. All of the movies featured here had a budget below $10 million. That includes inflation adjustments for older films like the first one ($1 million in 1954 comes out to $9.9 million in 2021). Preference is given to films that truly stay in one location and don’t stray from it except perhaps at the beginning or end when they’re on their way into or out of that setting.

Rear Window (1954)

There’s so much to see in a single place. In Rear Window, Hitchcock and his go-to cinematographer, Robert Burks, weaponize the act of looking. Dial M for Murder, their other 1954 collaboration with Grace Kelly, also sequestered itself in an apartment, but this one has a bigger window to the outside world. The Woman in the Window can only suffer in comparison as it invokes similar images of icy blondes and white-haired neighbors along with voyeuristic glimpses of across-the-street murder.

Right from the start, Rear Window trains the audience to watch and learn. After the opening credits, the camera floats out and surveys the courtyard, then the balcony and fire escape and apartment windows, where people get ready for work and sleep and brush their hair. Back inside, we see the sweat dripping from Jimmy Stewart’s brow, the 94-degree temperature on the wall thermometer, his broken leg and wheelchair, his own busted camera and wall of photojournalism highlights, and a darkroom negative that matches a nearby magazine cover. Even before a single line of dialogue is spoken, Hitchcock has parceled out enough visual information to communicate the character’s situation. It’s pure cinema.

12 Angry Men (1957)

Director Sidney Lumet made his feature-film debut with 12 Angry Men, which isn’t strictly a “courtroom” drama, since it’s the jury room where the movie is set. Henry Fonda plays Juror #8, who deliberates a murder trial with eleven of his peers. He’s the only one who isn’t ready to convict the defendant right away. The old Perry Mason TV series premiered the same year; I like to think its star, Rear Window’s Raymond Burr, was somewhere in the same courthouse, arguing a case of his own.

Made on a $337,000 budget (about $3 million when adjusted for inflation), 12 Angry Men is a good illustration of how a moving picture keeps moving even when it’s marooned in one place. To keep the film visually interesting, the camera mixes and matches characters and moves into different corners and spots around the table. It reduces the room to sections — a coat rack here, a window there, a restroom through that door — thereby changing locations within the same location and giving the eye new images to process. As the story progresses, it also tightens around the men’s faces, framing them more subjectively and ratcheting up the claustrophobia.

My Dinner with Andre (1981)

Andre Gregory and Wallace Shawn play fictionalized versions of themselves in this $475,000 two-hander set in the appropriately named Cafe des Artistes. On his way to the restaurant, Wallace’s voiceover builds Andre up as an enigmatic figure. He’s a theater director who left behind his family and career in Manhattan to go travel the world. Yet something’s gone wrong with him and maybe it all somehow relates to that Ingmar Bergman quote, “I could always live in my art, but never in my life.”

Brace yourself for a dialogue-heavy motion picture where the motion comes more from the characters’ mouths and the viewer’s brain. My Dinner with Andre does what it says on the tin. It sits you down for dinner with the eccentric Andre and lets him talk and tell stories and compare everything to the Nazis like the pre-Internet embodiment of Godwin’s law.

That may not sound like much of a movie plot, but Andre happens to be a gifted raconteur, capable of “painting word pictures on the imagination of the listener,” as Robert McKee noted in his book Story. His vivid monologues trigger one’s inner production designer so that we, in effect, construct mental set pieces of places like the Polish forest where he and a group of strangers apply method acting techniques to the self. At the heart of it is the question of what it takes to keep in touch with one’s humanity in the modern world.

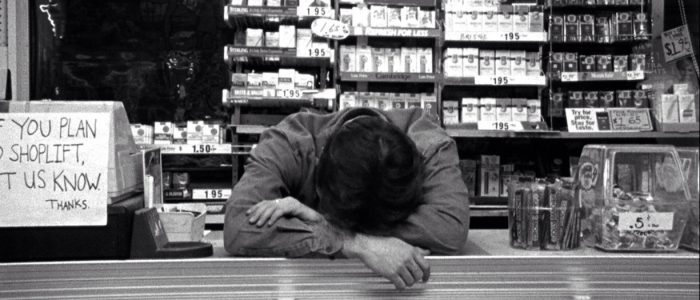

Clerks (1994)

Shot in black-and-white on a $27,000 budget, Clerks is unique in that the song licensing for its soundtrack cost more than the movie itself. Kevin Smith’s breakthrough indie feature — which is now in the National Film Registry — reimagines Dante’s Inferno as the life of a college dropout, wasting his potential while “jockeying a register” at a New Jersey convenience store.

The movie spends its first two minutes in Dante’s house before he gets called into work on his day off. Later, it makes another two-minute detour by car to a funeral wake. (We never see the actual wake.) Other than that, the entirety of the film takes place in and around the same building. Contrast this with its Miramax cousin, Reservoir Dogs, which is more liberal about venturing outside its main warehouse setting.

Dante works at Quick Stop and his best friend Randal works at a video store next door. They play hockey on the roof and wax philosophical about the independent contractors who died on the second Death Star. Each scene states its theme with a chapter heading that sounds like a circle of hell. “Purgation,” for instance, leads into a scene where Randal encourages Dante to vent his frustrations. The film’s frank discussions about “snowballing” and the definition of sex versus oral almost earned it an NC-17 rating. What’s funny is that they predicted the semantics of the Clinton–Lewinsky scandal, which would erupt in the news just a few years later.

Buried (2010)

At dinner, Andre Gregory talked about being buried alive. Here, we actually see that happen to Ryan Reynolds’s character, Paul, a civilian truck driver who awakens in a coffin underground after his convoy’s been ambushed in Iraq. Unlike The Bride in Kill Bill, Vol. 2, he’s not going to be able to punch his way out. He does have a lighter, however.

The film opens with black silence before we hear Paul moving around inside the coffin. He’s in a tight space, running out of air, and Buried holds the viewer in the same suffocating grip. It gives urgency to the horror-movie cliche of a phone with no reception. The coffin becomes a literal hourglass, filling with sand; and because this is a Lionsgate film, there’s even a bit of torture porn.

If you’re streaming Oxygen on Netflix and parts of it ring familiar, it’s probably because it hits some of the same beats as Buried (that spotty phone connection, calls to the cops and Mom, an animal in the box with our protagonist, the camera defying the box’s dimensions, pulling back in the darkness and X-raying it). Screenwriter Chris Sparling originally planned to make Buried for $5,000, so its $2 million budget almost feels extravagant, but at least some of that went toward the film’s music and title sequence, which keys it up as a polished, old-school thriller. Director Rodrigo Cortes cited Rear Window and other Hitchcock classics like Rope and Lifeboat as influences.

The Raid (2011)

There’s a whole sub-genre of single-location action movies that have cropped up since the original Die Hard. In The Raid, we’re a long way from one-liners and the skyscrapers of L.A. The budget is $1.1 million and the setting is a squalid Indonesian apartment block. It’s a drug lord’s stronghold, usually a no-go zone for police, but that doesn’t stop them from storming the building, anyway. The problem is, the shifty lieutenant who organized this particular raid has done so outside the purview of police command, which means there won’t be any backup coming after the bad guys lock the building down.

Marketed in the U.S. as The Raid: Redemption, this film was a gateway for global audiences into the ultra-violent world of Iko Uwais actioners. It’s not as much of a gratuitous bloodbath as his 2018 reunion with Joe Taslim, The Night Comes for Us, but there are still some gory moments.

One of the film’s strengths is that it builds character through action. Even secondary characters distinguish themselves through interesting choices. Yayan Ruhian, who appeared with Uwais in The Force Awakens, is especially memorable as Mad Dog, who isn’t afraid to set aside his gun and kill men with his bare hands. Nothing quite raises a villain’s threat level like putting him in a two-on-one fight, either. The hero, Rama, can hold his own, too: he takes on four guys with machetes at the same time.

Coherence (2013)

First-time director James Ward Byrkit shot Coherence at his own house over five nights—with a skeleton crew and eight improvisational actors. The most recognizable face is probably Nicholas Brendon of Buffy the Vampire Slayer fame, though you can also spot Hustlers helmer Lorene Scafaria in there beside stars Emily Baldoni and Maury Serling. The film had one of the smallest budgets on this list, $50,000, yet it brims with some of the biggest ideas. It’s not the only dinner-party movie here, nor is it the only film where characters meet duplicates of themselves; but it is the only one that had no script, just an elaborately plotted outline.

The intention was to bring a spontaneous, naturalistic feel to a science fiction thriller in which a passing comet splinters reality and keeps a group of friends looping back on the same location (or some parallel-universe copy of it). If you can forgive the occasional leap in logic, dialogue-wise, you’ll find yourself getting caught up in a real mind-bender.

The One I Love (2014)

A two-hander becomes a four-hander when Ethan and Sophie (Mark Duplass and Elizabeth Moss) encounter their doppelgangers on a retreat at a weekend hideaway. It’s meant to be a form of couples therapy but complications ensue when Sophie starts falling for the other Ethan, who represents a more ideal version of her husband. Call it The Stepford Spouses.

Estimated budget: $100,000. Ted Danson, who appears in the first scene as Ethan and Sophie’s therapist, and Mary Steenburgen, who does a voice cameo as Ethan’s mom, lent their real guesthouse to director Charlie McDowell (Steenburgen’s son from her previous marriage to actor Malcolm McDowell.) Justin Lader’s screenplay teases the idea that the not-so-happy couple is stepping through the door to another dimension. If so, it’s one that comedically reflects the themes of another 2014 thriller, Gone Girl. People put on their best face to attract a partner but what happens when they drop the picture-perfect facade and their partner has to live with their true self?

The Invitation (2015)

If you feel some deja vu during The Invitation’s cold open, it may be because it fades in on a scene similar to one from another horror movie that came out two years later. That would be Get Out, which also put us in the car with an interracial couple as they hit an animal on the road. In The Invitation, it’s a coyote instead of a deer and the driver, Will, puts it out of its misery with a tire iron.

That sets the tone for a $1-millon thriller about dealing with grief and the loss of loved ones. Logan Marshall-Green sports a Jesus beard as Will and he’s headed for a Last Supper where the wine flows red—and the guests might, too. There are twelve of them, like the Apostles, though one is suspiciously MIA.

Unlike Get Out, The Invitation doesn’t cut to comic relief in the outside world. It stays right there in one Hollywood Hills home and lets us share Will’s perspective and feel the destabilizing effect of his anxiety. At this party, Manson-girl attire is accepted and the tension is thick even before Will articulates, “Something bad is happening here.” It’s all in service to a nail-biter that enabled Karyn Kusama to escape director’s jail and make Destroyer with Nicole Kidman next.

Wheelman (2017)

Frank Grillo was once tapped to star in a remake of The Raid. (It’s no longer a remake.) Here, he stars as an unnamed getaway driver who finds himself in over his head when the bank robbery he’s involved in doesn’t go according to plan. Like Toshiro Mifune in Yojimbo, he’s soon caught in the middle of a mob war.

Wheelman puts a $5-million, action-oriented spin on the premise of a film set entirely in a car. The talky Tom Hardy vehicle, Locke, famously nurtured the same conceit but it hinged more on the speakerphone drama of a man’s personal and professional life unraveling.

In Wheelman, the stakes are life-or-death, fought over pulse-pounding shootouts and car chases. The movie makes things interesting by letting people in the car with Grillo (who’s more grizzled, less baby-faced, than other 2017 drivers) and it takes advantage of the windshield and windows to show outside action. Technically, the car visits numerous places, so maybe we’ve bent the one-location rule, here at the end. However, the only time the passenger-like camera exits the vehicle is for a few exterior shots and one climactic car switch.

The post 10 Single-Location Movies That Show You Don’t Need a Big Budget to Tell a Good Story appeared first on /Film.

0 Comments