“Dying isn’t simple is it?”

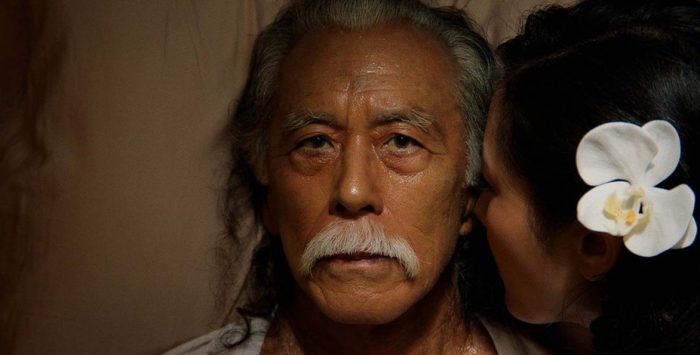

Masao (Steve Iwamoto) is on his death bed, unwilling — or unable — to reckon with his debilitating sickness, even as his estranged children and grandchildren flit around and away from his bedside. The only presence that has stuck by his side the entire time he’s been bedbound is not a physical one: it’s the ghost of his long-dead wife, Grace (a beatific Constance Wu), who had arrived soon after the formerly robust, dynamic Masao had received his diagnosis, looming on the outskirts of his isolated house before finally being allowed entrance by her frightened husband. As Masao waits to die, his spectral wife guiding him through his final days, Christopher Makoto Yogi‘s elegiac family drama I Was A Simple Man crafts a haunting tapestry of a man’s life, interwoven with Hawaii’s own post-colonial landscape, highlighting and embracing the scars that are left behind by both.

There’s a leisurely feeling to the first half of I Was a Simple Man, with cinematographer Eunsoo Robin Cho (who worked with Yogi on his debut feature August at Akiko’s) shooting in wide lenses and deep focus, letting the vast expanse of Hawaii’s floral landscape swallow up our characters as they serenely roam about onscreen. But already there’s a hint of the uncanny about it: on the fringes of this pastoral idyll are the looming towers of concrete and the ever-present drilling that marks the gaining tourist industrial complex.

“Remember when this was all beautiful green?” Masao’s equally world-weary, and equally cool, friend remarks to him as they share a cigarette and overlook the concrete city from within a drab parking garage.

Masao still lives in that beautiful green, for now, in the far-off countryside near the north shore of O’ahu, isolated from most everyone except for his beloved dog and the longtime friend (Akiko Masuda) who visits him every now and then with a growing note of concern in her voice. Masao seems content, at first, to live this hermit-like existence, hanging up his laundry, feeding chickens, wandering through the wide-open spaces that this rural livelihood affords. But late at night, he stares mournfully at the altar of his long-dead wife and spontaneously calls his estranged son Gavin on the mainland, who is quick dismisses his lonely father.

Yogi quotes philosopher Jacques Derrida’s line “There is no world, only islands,” as inspiration for the film — a phrase that rings painfully, lovingly true in I Was a Simple Man. Masao has created his own island of solitude in choosing to live in his countryside home and in his distancing himself with his children after his wife’s death. But Hawaii, a state famously made up of only islands, is the flip side of this: a collection of masses of land that are somehow still united and in harmony. It’s the connection between the man and the land that Yogi hones in on in I Was a Simple Man, charting Masao’s troubled life and final days alongside Hawaii’s own turmoiled history.

Reminiscent the rich naturalism of Yasujiro Ozu meets the heady surrealism of David Lowery’s A Ghost Story, I Was A Simple Man unfolds as a tableau of past and present, speaking in tandem to each other across space and time. The awkward realism of the family drama, between Masao and his adult children (played mostly by non-actors) who don’t quite know how to speak with him, gives way to a surreal journey through memory — Masao’s memories? The memories of the cultural landscape of Hawaii? Who knows? They may in fact be connected, we learn, as we meet a younger Masao (Tim Chiou, all brooding masculinity), mourning the death of his wife at the bottom of a glass in some seedy bar. We start to piece together why his kids bristle at the elderly Masao’s fond recounting of their childhood, as the younger Masao pushes away his children, sending them to live with an aunt on the mainland. We begin to see more of a complete picture still, as the film lazily wanders back to the days of teenage Masao (Kyle Kosaki) and Grace (Boonyanudh Jiyarom, bearing a striking resemblance to Wu), when they first fall in love in post-World War II Hawaii.

As the film wears on, I Was A Simple Man begins to be untethered from the earthy naturalism that defined it early on, and becomes adrift in time, as if we’ve become privy to the wandering mind of a dying man. The film is at first loaded with apprehension — Masao resisting and repeatedly responding to Grace, “I’m not ready yet,” as the cacophonous strings of the film’s delicate score grow louder and more discombobulating. But as his memories and reality begin to collide, his past and present selves literally staring at each other across time in one particularly eerie sequence, the creepy feeling gives way to something more tranquil. That feeling of serenity — which filled every frame at the beginning of the film — slowly returns, a peaceful contentedness creeping back. A contentedness for his life, and how it was shaped by Hawaii, a region that had changed so much since he arrived as a young child from Japan, and continues to change still. And through this ghostly journey, Masao learns to embrace the scars of his land — still standing after the plantation owners, the bombs, and the tourists have gotten their hands on it — and of his own troubled past.

I Was a Simple Man is a slow-burning walk toward the light, a paean for life, and the land and people that shaped it. It’s the kind of love letter that only a lifelong resident of Hawaii like Yogi could make, to a resilient land whose scars will take long to heal.

/Film Rating: 9 out of 10

The post ‘I Was a Simple Man’ Review: A Ghostly Constance Wu Guides Her Dying Husband in a Gentle Meditation on Life [Sundance 2021] appeared first on /Film.

0 Comments